Hip Disorders

What are Hip Disorders?

Hip disorders can affect one or both hips and are sometimes apparent at birth or develop during childhood. Scottish Rite for Children treats thousands of patients every year with the following hip conditions:

- Developmental Hip Dysplasia

- Adolescent Hip Dysplasia

- Perthes Disease

- Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

- Femoroacetabular Impingement

Other common hip conditions treated by our experts:

- Transient synovitis of the hip

- Sickle cell disease affecting the hip

- Avascular necrosis of the hip

- Bone dysplasias affecting the hip

- Sports related injuries of the hip

- Avulsion injuries of muscles around the hip

- Hip dislocation due to Downs syndrome

- Hip subluxation and dislocation due to cerebral palsy

- Hip dysplasia due to Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

About Hip Disorders

Hip discomfort is a common issue for growing children. Often, pediatric hip pain is a result of the child’s activity level, as too much or too little exercise can cause aches and pains. However, in some cases, hip pain and other symptoms can be signs of a more serious condition. Some hip disorders are present at birth, while others develop during childhood. One or both hips can be affected.

It’s important to be aware of the signs of hip disorders so you know what is normal and when your child might need to see a doctor. Some general symptoms of childhood hip disorders include:

- Limping when walking

- Pain in the hip, groin, thigh or knee when the child is active

- Reduced movement or range of motion in the hip

- Refusing to stand or walk on a certain leg (for toddlers)

If your child is experiencing persistent pain or is having trouble walking or doing daily activities, make an appointment with a pediatric orthopedic specialist. If your child shows any signs of a hip infection, such as fever and refusal to use a certain leg, go to the emergency room.

At Scottish Rite for Children, our experts treat thousands of patients every year with the following hip disorders:

- Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH): This is a condition in which the hip joint does not form correctly in babies or young children. The femoral head, which is the “ball” part of this ball and socket joint, is partially or completely out of the hip socket. DDH is diagnosed within the first few months of a baby’s life, but it can sometimes go unnoticed until the child is of walking age or during adolescence (adolescent hip dysplasia). It can cause irregular leg length (one leg longer than the other), pain, a clicking or clunking sound in the hip when examined, limited range of motion and limping, among other symptoms. Risk factors for DDH include family history, being female and being in a breech position when in the womb.

- Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: Sometimes referred to as Perthes disease, this condition disrupts the blood supply to the femoral head part of the hip joint, causing all or part of the bone of the femoral head to die from lack of blood flow. The joint becomes weak, and new bone replaces the dead bone over a one- to two-year period. Signs of Perthes disease include pain with activity, limping, limited range of motion and stiffness.

- Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: This disorder usually appears during the teenage years, when the thigh bone grows at a fast rate. It causes the ball part of the thighbone (the capital epiphysis) to slip off the growth plate at the top of the thighbone, leading to pain or limping.

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI): In this condition, excess bone grows along one or both bones of the hip joint, giving them an abnormal shape and preventing the ball from fitting in the socket properly. FAI can cause pain in the hip, as well as in the back, outside or lower side of the hip or thigh.

We treat many other hip disorders, including:

- Avascular necrosis of the hip: Also called osteonecrosis, this can occur when the femoral head doesn’t get enough blood flow or oxygen, leading to the death of bone cells. This condition can cause severe pain and the development of early arthritis of the hip joint.

- Sports-related hip injuries: These can include avulsion injuries of muscles around the hip, fractures and other injuries. Adolescents are at greater risk for certain hip injuries.

- Transient synovitis of the hip: Also called toxic synovitis, this condition causes swelling and inflammation in the tissues around the hip joint. Over time, children with this condition can develop a limp or have trouble standing.

- Hip disorders related to other conditions: Children with Down syndrome and cerebral palsy are at higher risk for hip disorders, such as dislocation and hip dysplasia, due to issues with the muscles that hold the hip joint in place. Other conditions, such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, can also lead to hip problems.

Our goal is to help your child return to their active lifestyle as quickly as possible. Our experienced orthopedic specialists are dedicated to providing the latest treatment options and offering individualized care for every patient.

Treatment options depend on your child’s age, symptoms, diagnosis and results of imaging. Available treatments include:

- Corticosteroid injections: This category of anti-inflammatory medications can help relieve pain and symptoms of inflammation.

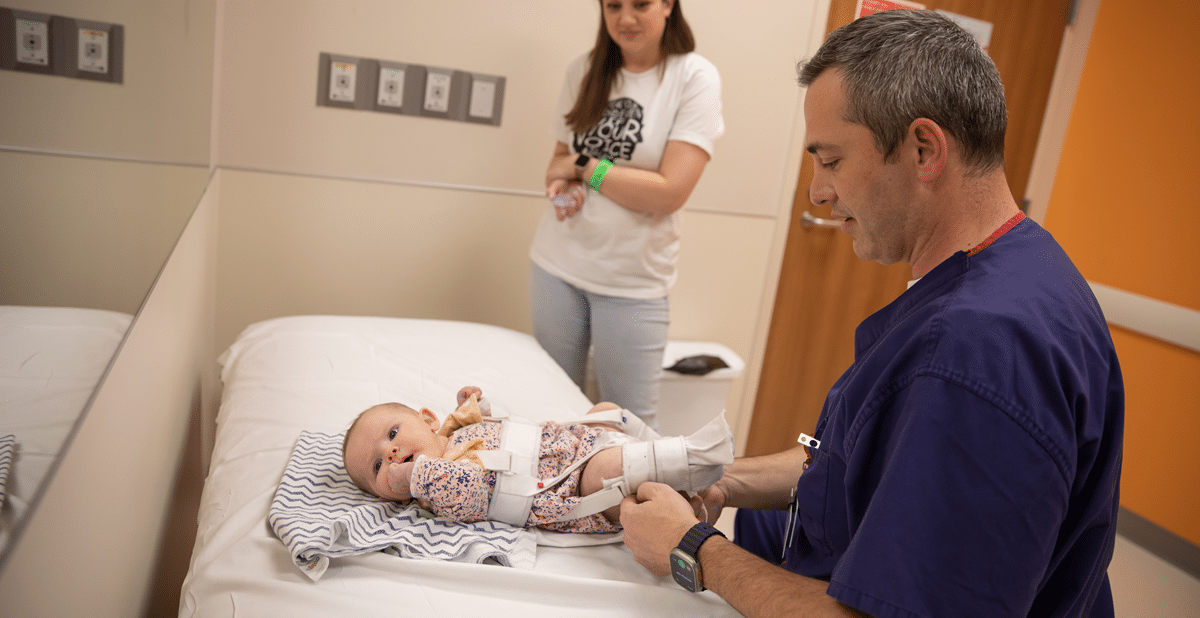

- Pavlik harness: This is a soft splint that can be used to hold the hip joint in place in babies under 6 months of age who have been diagnosed with DDH.

- Physical therapy: Certain exercises can strengthen the hip joint muscles, improve range of motion and ease symptoms.

- Surgical treatments: Our expert orthopedic surgeons perform a range of procedures to correct severe hip disorders that don’t respond to other interventions.

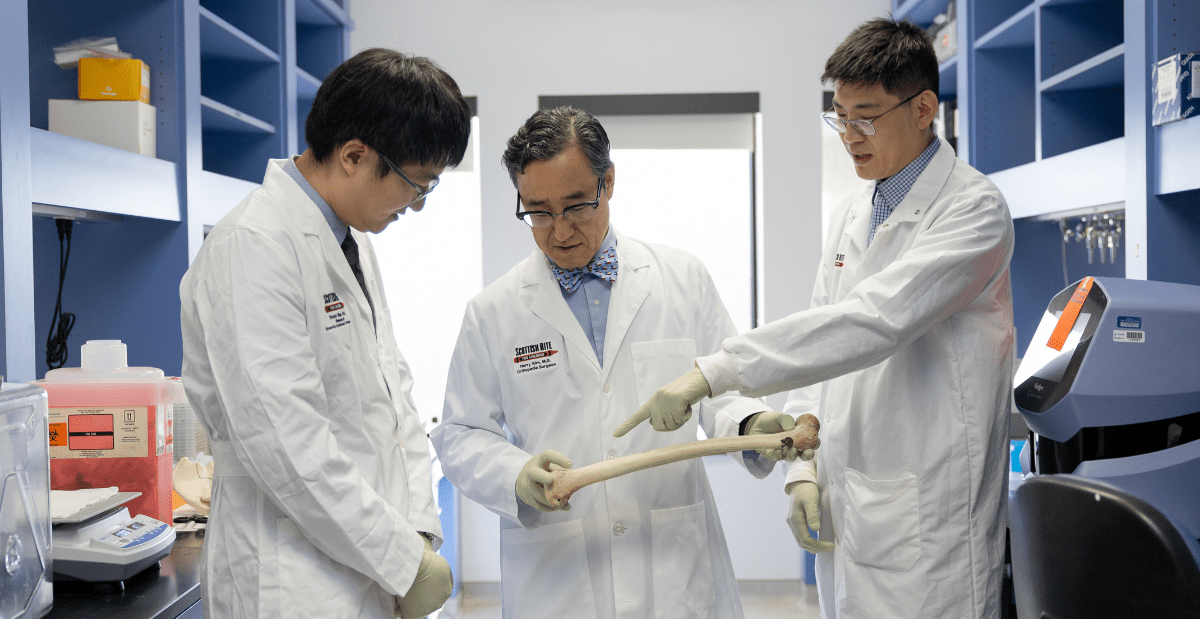

Researchers in our Center for Excellence in Hip are committed to advancing research associated with pediatric hip disorders.

Current studies include:

- Prospective Infantile DDH Registry: This study evaluates babies younger than 1 year who are referred for DDH-related hip abnormalities. The goal is to determine optimal methods of evaluation and treatment.

- International Perthes Study Group: This multicenter study involves more than 40 participating institutions across the country. The purpose is to compare the outcome of Perthes disease treatment methods for three different age groups.

- Prospective Evaluation of Hip Preservation: This study examines the radiographic, clinical and functional outcomes of hip preservation surgery in adolescents and young adults.

Bondy's Story

Bondy came to Scottish Rite for Children to be treated for hip dysplasia. Her hip socket did not cover the ball of her upper thighbone, which caused the dislocation. Bondy underwent surgery and wore a cast for 16 weeks.

Our Experts

Harry Kim, M.D., M.S.

Henry B. Ellis, M.D.

Elizabeth W. Hubbard, M.D.

William Z. Morris, M.D.

David A. Podeszwa, M.D.

Daniel J. Sucato, M.D., M.S.

Lane Wimberly, M.D.

Alexandra K. Callan, M.D.

Shawne Barron, M.S.N., APRN, PCNS-BC

Diana Halback, M.S.N., CPNP, RNFA

Emily Holmes, CPNP-PC, A.C.

Andrea Pendleton, CPNP-PC

Share your story

YOU HAVE A STORY. WE WANT TO HEAR IT.

Sharing your experiences at Scottish Rite for Children can provide inspiration to other patients and shine a light on our mission of giving children back their childhood. Whether you’re a current or former patient or family member, we invite you to share your story with us!