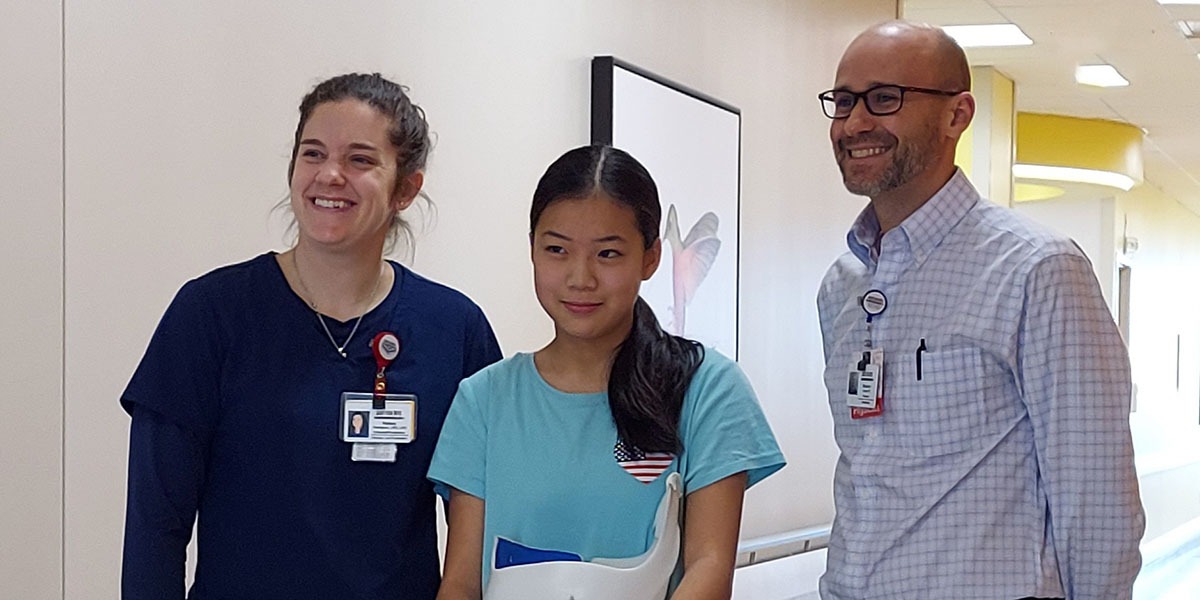

A few weeks after surgery, Ayden and his family reunited with Dr. Gill at Scottish Rite for Children Orthopedic and Sports Medicine Center in Frisco. They also met the multidisciplinary team of experts who would care for Ayden, including pediatric psychologist

Emily Gale, Ph.D., prosthetist Dwight Putnam, C.P., L.P., and occupational therapist Lindsey Williams, O.T.R., C.H.T. “When you lose a limb, the family goes through a process of grief,” Dr. Gill says. “So, it’s really important for our Psychology team to work with them early on.” During his recovery, Ayden and his family toured the Prosthetics Lab at the Dallas campus to learn about the possibility of wearing a prosthetic arm and how it could be customized for him. “It was important for Ayden to know that whether he has a prosthesis or not, it does not define him,” Dr. Gill says. “He could do things with it or without it, but he was going to be great regardless.” Ayden decided to move forward with the arm. After his limb had time to heal, he would return for an evaluation with Dwight. In the meantime, Ayden began occupational therapy with Lindsey twice a week. Initially, she focused on caring for his residual limb, including massaging his scar to desensitize the limb in preparation for wearing a prosthesis. “The day I met Ayden, he was very quiet,” Lindsey says. “He was trying his best, but he didn’t yet know the potential that he had. We were just trying to get rid of his phantom limb pain, trying to cope in that way.” Phantom limb pain occurs when the brain perceives tingling and painful sensations in the limb that is no longer there. To resolve the pain, Lindsey used mirror therapy to trick his brain into thinking his right hand was there. Because Ayden lost his right arm, and he was righthanded, they also focused on dominance retraining, or training his left hand to become the dominant hand. They worked on strengthening the grip of his left hand, as well as coordination, fine motor skills and handwriting.