Read the original article on the DFW Child website here.

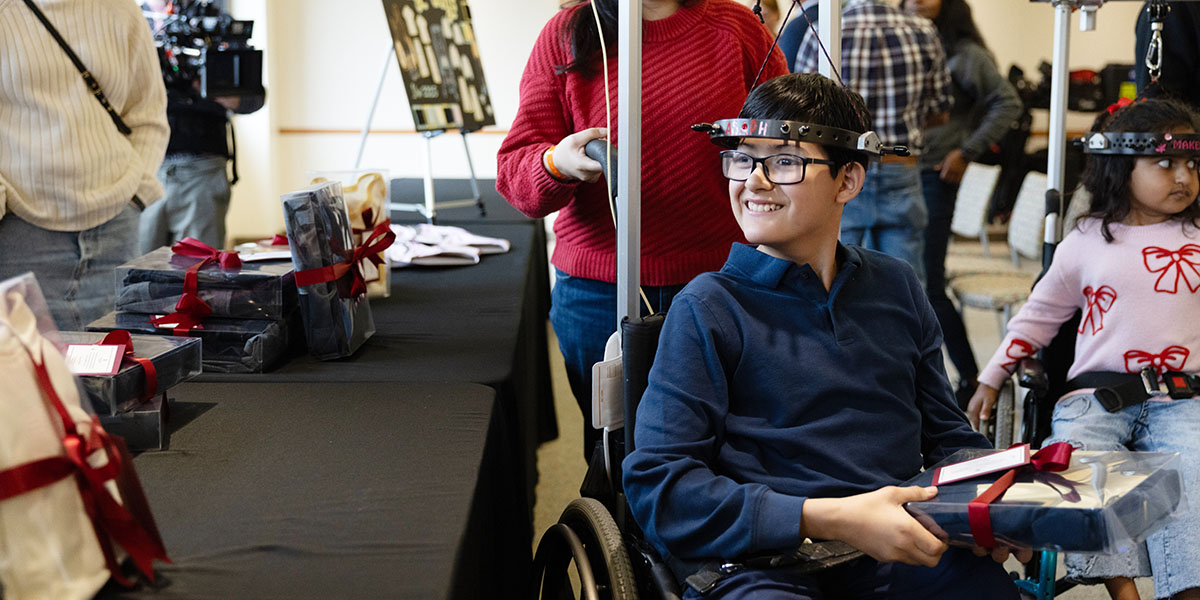

From the time he was a toddler, Jamie Maness was a burst of energy.

“Climbing on everything, getting into everything, risky behavior, no fear,” his mother, Debbie Maness, says.

When the Plano boy was 6 years old, he was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) combined type, the most common form of ADHD. About 5 percent of children in the U.S. have ADHD, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The disorder manifests in three main symptoms: impulsivity, inattention and hyperactivity. Kids with ADHD combined type show all three.

“He was never aggressive or anything—it was more about the level of activity and always being on the go,” Maness says. “He’d always dart in front of cars and didn’t have a sense of fear.”

Like many parents, Maness thought sports would be a good outlet for her son, who’s now 11. So since kindergarten, Jamie’s been involved in everything from taekwondo and soccer to flag football. He has practice once a week and also has weekly games. When he’s active, Maness sees a marked difference in his behavior. “When he’s playing sports and the days he’s practicing or playing games, he goes to sleep earlier and easier,” she reveals. “The days he doesn’t, it takes a long time for him to wind down.”

For kids with ADHD, sports tend to have a calming effect, confirms Joy Crabtree, a child psychologist at Cook Children’s in Fort Worth. “In terms of ADHD, [sports and exercise] can provide an outlet for excess energy,” she says. “It can provide an outlet for frustration. A lot of these kids certainly do have a low frustration tolerance.”

The benefits of sports are well-known: For all kids, sports can boost self-esteem, help them learn teamwork and problem-solving skills, provide physical activity, reduce stress and improve their academic performance. And there is documented evidence that children with ADHD in particular have a lot to gain from sports and exercise. A study published in the Journal of Pediatrics in 2012, for instance, found that even a short bout of exercise can eliminate distractions and help children with ADHD perform better on academic tasks. “He also does better with school when he’s playing sports,” Maness says of Jamie. “His grades are better, his focus is better. It’s helped being able to have that focus and confidence.”

But in recent years, researchers have begun to uncover that sports can also have negative implications for kids with ADHD—namely a greater risk of injury and a longer recovery.

The question for parents, then, is: How can my child reap the benefits of sports while staying safe?

THE GOOD

Richardson 13-year-old Jansen Morris started gymnastics classes at 18 months. At 6 years old, she joined a competitive team and now trains 32 hours a week. Her brother Hudson, 10, plays baseball, soccer and lacrosse.

“He likes the variety of the different sports, always doing something different,” mom Shalon Morris says. “Whereas Jansen, doing competitive gymnastics, it’s really all or nothing.”

Both siblings have ADHD. Jansen’s manifests as inattention, whereas Hudson is more hyperactive. But he doesn’t have risk-taking behavior—he’s a rule-follower, Morris says. Jansen tends to be more withdrawn and unfocused but also more likely to push boundaries, to be more impulsive.

Despite the differences in their ADHD symptoms, participating in sports has been incredibly beneficial for both, their parents believe.

“The time [Jansen] spends at the gym is really beneficial for her and her diagnoses,” Morris says. Because she generally moves from one thing to the next, the sport has helped her to maintain attention, since it’s a sport that requires extreme focus.

“[The research] tells me, if they’re allowed to move and they’re allowed to have breaks to get up and move, they can refocus,” Morris explains. “It gives them a reset. They can only focus for so long before their attention fades.”

“I see it in my office,” Crabtree says of her own clients. “When I see [kids with ADHD] having a really hard time focusing on a conversation with me, I pull out a stress ball or play catch with a ball, I see their ability to focus with me improve.”

For Hudson, who is more hyperactive, playing sports “really helps him get out that energy,” Morris says. “Some kids with ADHD also need a little extra attention with social skills, and sports helps him get out of the comfort zone.”

THE BAD

But those same factors that make sports a good match for kids with ADHD—that is, movement, action, interactions with other players—can also make these kids vulnerable to injury.

According to researchers from the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, there is no direct correlation between ADHD and the likelihood of injury. But because young people with ADHD tend to exhibit impulsivity and reckless behavior, the researchers say, they are at greater risk of getting injured.

In a study published last year, the team from OSU analyzed more than 850 athletes over a five-year period and found that athletes with ADHD are twice as likely to compete in team sports and 142 percent more likely to participate in contact sports like football, hockey and lacrosse—in other words, sports that pose a higher risk of injury in the first place.

The results of the study aren’t surprising to Crabtree. “It makes sense to me that kids with ADHD might choose team sports as opposed to individual sports, probably because there’s more going on in team sports,” she says. “There’s more activity, more stimulation. It might be more interesting.”

And within their chosen sports, their symptoms can up the ante even more. For kids with ADHD inattentive type, like Jansen, a lack of focus or concentration can lead to accidents. Jansen’s parents admit that she does have a hard time following directions and following through, which has caused issues with her coaches. For a child who struggles with staying on task and following instructions, gymnastics in particular can be a challenge.

“There’s a concern for safety more than in other sports,” Jansen’s father, Michael Morris, says. “It’s definitely something we’re aware of. We have talked to the doctor about [how to help her realize] she has to be firing on all cylinders.”

Meanwhile children with ADHD combined type are impulsive and tend to make careless mistakes—a bad combination when it comes to safety.

“When you’re talking about ADHD combined type, those kids are more impulsive by nature, by definition of the diagnosis,” Crabtree explains. “When you’re talking to parents about traits, [you hear], ‘They jump off the bed all the time,’ or ‘I’ll look away for a minute and they’re trying to jump off the roof into the pool,’ or ‘They’re climbing on the counters.’”

So when kids are playing team sports that are more aggressive and competitive like football, it makes sense that their symptoms put them at greater risk of injury. “It seems kids with ADHD tend to be more risk-taking overall, and my thought is that these are also going to be the kids who are diving for the ball or trying to go for the extra base,” Crabtree says.

Because children with ADHD are easily distracted and display risk-taking behaviors, injury is a common theme, even outside the realm of sports, according to Shane Miller, a sports medicine physician who works with children of all abilities at Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children. “They often will present to the emergency department with injuries,” he says. “Both of these [traits] may contribute to on-field injuries.”

The research is borne anecdotally: Concussions are one of the more common sports injuries, and one of the more serious. At Scottish Rite, about 12 percent of patients are treated for concussions report a history of ADHD, Miller says, which is about double the rate of ADHD in the general population.

And when kids with ADHD experience a concussion, they are at greater risk of persistent anxiety and depression compared to athletes who don’t have ADHD, researchers presented this summer at the American Academy of Neurology’s Sports Concussions Conference. That study suggests athletes with ADHD should be closely monitored post-injury—preferably, Miller adds, by professionals with experience working with children with ADHD.

“As far as concussions go, we do see there’s an increased risk of injury and that [kids with ADHD] may take a little longer to recover and have more symptoms,” Miller agrees. “It’s a little unclear why. But we certainly pay attention when there’s a disability or learning difference. Those problems are generally associated with longer symptoms.”

While the latest research surprised Maness, fear of injuries is why she chose to put Jamie in flag football instead of the full-contact version.

“I didn’t want him to go directly into football,” she says. “I wanted him to have knowledge before he goes into it. […] If he was in high school football, I’d be a little worried about him playing. [Safety is] the reason I chose flag football. I figured they still make kids wear mouthguards.”

Recently, Maness says Jamie did get injured in flag football, but it was a result of colliding with another child. His mother says the incident has made her rethink letting him eventually play tackle football—and Jamie may feel the same way.

“He didn’t like that he was going to be in flag football because he couldn’t tackle, but after being in that crash, he will likely think twice,” she says.

THE RIGHT FIT

Even knowing the risks, children with ADHD shouldn’t avoid sports, Miller says. “There are tremendous benefits to athletics for all children,” he explains. It’s a matter of finding the right fit for your child’s abilities and understanding the precautions you’ll need to take.

Experts agree that parents and their child’s doctors can work together to find the best sport for the child and figure out how to avoid injuries. Miller encourages, for example, what he calls early sports sampling—in other words, trying a lot of different sports early on in their childhood to see what suits their abilities and likes.

“Different sports carry different risks,” Miller says. “We try to individualize the sport to the child’s needs and abilities and determine what’s best for them. Not every child with ADHD is going to have the same skills.”

And their symptoms may not always be a hindrance in the realm of sports. In Jansen’s case, her impulsiveness hasn’t caused injury; in fact, it might have even helped her succeed in gymnastics, Shalon says. “At a very high level, a lot of girls develop blocks or fears because they’re doing things like triple backflips,” she says. But Jansen “doesn’t seem to show any fear.”

In fact, sports could even be a good starting point as far as treatment, but it’s best to check with mental health providers to gauge how well an activity is working and whether it needs to be used in combination with other treatments. “For some kids, it may be enough,” Crabtree says. “But it depends on many factors.”

Miller suggests that if a child’s ADHD symptoms are better controlled with other treatment, they might be less at risk of injury.

Once a child decides on a sport, Michael Morris recommends that parents maintain a good working relationship with the child’s coach because they too can watch for symptoms and provide additional support.

“It is definitely a blessing to have coaches that are so focused on her own well-being,” he says of Jansen’s gymnastics program. “They pay close attention to how [Jansen’s] functioning that day,” They’ve sent her home when she’s ‘just not here’ this afternoon. That’s rare, but it’s a safety issue.”

He believes this has helped his daughter avoid injuries.

“That’s probably the most important thing parents can do. Have a good working relationship with a coach,” he adds.

Coaches have also been integral to Jamie, acting not only as safety nets but also as mentors, in a way, as they help him improve his behavior. “If he’s having a bad day behaviorally, the coaches step in to set guidelines,” Maness says. “Having him in sports, you have an added person to say, ‘You need to go through the rules and be respectful.’”

As he grows up, Maness says she expects to watch how Jamie does in sports to decide whether continuing football—a sport with a high injury rate even without factoring in ADHD symptoms—is the best decision.

But so far, she says, despite the risks, sports have been good for her son. “I knew from the get-go that him having an outlet outside of school was important to get that physical energy out,” she says. “The benefits outweigh the risks … that’s what we’ve experienced so far.”

CONCUSSION CONCERNS

There is a lot doctors don’t know about concussions, says Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children sports medicine physician Shane Miller. A concussion is a mild form of traumatic brain injury that occurs when a blow causes the head to rapidly move back and forth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Though usually not life-threatening, the injury does take time to recover—for some populations, like those with ADHD, longer than others.

What medical experts do know is that sports and recreation are the leading cause of concussion emergency room visits among children and teens, according to a CDC report. In addition, some sports carry a greater risk for injury.

A 2013 study from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine found that the sports with the highest incidence of concussion are football, hockey, rugby, soccer and basketball.

But at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, researchers presented these findings from high school data over a 10-year period:

Girls are about twice as likely as boys to get a concussion.

Girls soccer had a higher rate of concussion than boys football from 2010–2015. Researchers suggest this is due to the emphasis on contact and the lack of protective gear.

Girls soccer had the highest rate of concussions among sports in the study during the 2014–15 school year.

From 2005–2015, there was a significant increase in concussions in both boys baseball and girls volleyball.