Get to Know our Staff: Anthony Minopoli, Clinical Research

What inspired you to apply for the CORA/MSRF position?

My passion and lifelong goal, since I was a kid, was to become a physician. Over the years, I have done everything I could to help achieve that goal. With my senior year at Auburn University ending, I wanted to find an experience that aligned with my goals and values, but that also helped best prepare me for applying to medical school. I am not originally from Texas, but through my college years, it became a second home thanks to some of the connections I made along the way. Whenever I expressed my goal to go into medicine, it was also followed by the same question, “Have you heard of Scottish Rite?”

When I came across the CORA position here at Scottish Rite, I knew it was the perfect match. It presented unparalleled opportunities for clinical research and shadowing and the chance to form profound career connections. Simultaneously, it aligned with my interest in orthopedics, but in a new light, where I get to make an impact on the lives of children. The most unique aspect of this position is the overwhelming support of your peers, team and Scottish Rite as a whole. They understand your goals, want you to succeed and challenge you to grow and learn as much as possible.

Have you always been interested in medicine and/or research?

Before I decided to pursue medicine, I knew that I wanted to help others. The most fulfilling thing to me was putting a smile on people’s faces knowing I impacted their lives for the better. Whether it was the numerous injuries I suffered in sports or witnessing my family battle with their own health struggles, I idolized and admired the impact physicians had on my life and the people I care about.

During my senior year at Auburn University, I worked in the Sports Biomechanics research department. I started this initially to fulfill the credit needed to graduate, but I never expected to love it as much as I did. It taught me to think critically, to question and to learn from my failures to find answers. It was this experience that sparked my passion for research and led me to Scottish Rite.

What is it like working at Scottish Rite for Children?

Working at Scottish Rite has been the most fulfilling experience of my life. I am currently a part of the Foot and Ankle team where I am surrounded by peers and mentors who challenge me each day. I not only get to learn, but I am also given the responsibility to handle tasks and problems that, although were daunting initially, have helped me grow as a researcher and aspiring physician. To top it off, I get to interact with the physicians and their patients who count on us to help give them back their childhood.

Can you share a few sentences about someone at Scottish Rite who has been a mentor to you and how they have impacted your experience? What project are you working on with that mentor?

As a part of the Foot and Ankle team, I work closely each day with Dr. Anthony Riccio. In the short time I have been here, we have worked on improving the robust Foot and Ankle and Clubfoot Registries that he developed. Additionally, I worked with him and our Foot and Ankle MSRF, Taylor Zak, to complete the Idiopathic Toe Walking Study.

Another project I am proud to discuss is one I have been able to lead in conjunction with Dr. David Podeszwa. This study will analyze the long-term outcomes of patients treated with Distal Femoral Osteotomies. In this study, I will be working closely with Scottish Rite’s Center of Excellence for Limb Lengthening and Reconstruction.

How do you think this experience will impact your career path?

In the short time I have been here, my anticipated career path has already changed. Although I have always been interested in orthopedics, since working at Scottish Rite I realized just how much I enjoy working with the pediatric population. I hope to specialize in pediatric orthopedics and continue playing an integral part of clinical research. Scottish Rite is a renowned pediatric research hospital, and I now recognize the vital role research plays in providing the best possible care to our patients.

What progress have you made towards your career goal since beginning the program?

I am currently in the middle of the medical application cycle! So far, I am grateful to have interviewed at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the University of South Alabama, and the Uniformed Services University, and hopefully many more.

What is your favorite project that you are currently working on or have worked on at Scottish Rite?

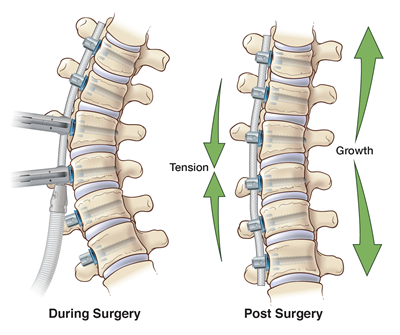

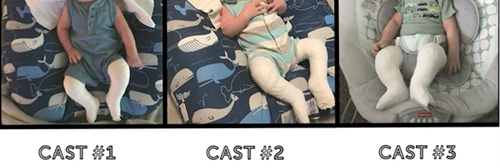

I am working on numerous projects currently, but a few stick out from the rest. The most fulfilling study to work on is Dr. Riccio’s Clubfoot Registry and the sub studies involved with it. This study requires me to spend a great deal of time in the clinic working with Dr. Riccio and the team. While Dr. Riccio treats the kiddos, I get to monitor the pain and temperament of the babies throughout the process. In the short time I have spent here, I have developed a newfound passion for working specifically with young kids and their families.

What advice do you have for future CORA/MSRF participants?

The best advice I would give to future CORA/MSRF participants is to take full advantage of the opportunity. Scottish Rite is unique to any other hospital I have worked in. Everyone, whether they know you or not, cares. Do not be afraid to reach out for advice. Take the time to find mentors and step out of your comfort zone to develop relationships with those you admire. Especially in the CORA/MSRF programs, your peers understand your goals and want you to succeed. Use the people and resources at your disposal to pursue passions and experiences that you find interesting.

What is one thing most people don’t know about you?

In the middle of Dallas, Texas, the one thing people never expect is to find out I am an avid Washington Commanders fan!

Anything else you would like to add?

I just want to thank everybody at Scottish Rite for giving me this opportunity. It is rare to find an experience that you wake up and are excited to be a part of each day. I have learned more in these few months than ever before, and I could not be more grateful to be a part of this team!