Blog written by Megan, Garrett’s mom

In June 2022, Garrett developed a limp and complained about his right knee hurting. We went to his pediatrician for an X-ray after a few weeks of not getting any relief. He had just attended a basketball camp and is active in many sports.The knee X-ray in June showed no damage, sowe started some chiropractic care to stretch and see if we could determine what was causing his pain. After 6 weeks, nothing changed. Garrett would say that his hip was “tight,” but he said there was no pain.

Garrett had an MRI in August so we could determine the next course of action. It was in the MRI that it was discovered his femoral head was quickly deteriorating, and he had Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. We went to a local hospital for a consultation, and my son was told not to walk on his own without the help of crutches. The word “nonweightbearing” was seared into our brains.

He started school four days later, and we had to urgently contact his school’s administration to discuss accommodations for him. There was so much anxiety about attending school on crutches and being asked questions. Garrett didn’t want to tell anyone what was going on, and I dreaded the school year knowing this was going to be the most challenging thing he’d ever faced.

While our local health care options are great, we wanted to get a second opinion since this was such a devastating diagnosis for such an active and energetic kid. I started reading everything I could on Perthes disease. I was up late one night researching the disease, and I found some videos featuring Dr. Harry Kim with Scottish Rite for Children. He just seemed to be the expert in this condition, and I wanted nothing but the best care for my son.

I requested an appointment online, and we were contacted the next day. Although we live nine hours away, we jumped at the chance to travel to Dallas and get a second opinion. I wanted to talk to a nurse to make sure we really should travel to see Dr. Kim. Despite some doubts, something kept gnawing on me to keep pushing. Dr. Kim’s nurse, Kristen, called me a few days later, and we talked about the situation. She asked me to get the X-ray and MRI files to her for Dr. Kim to review. Soon after, she called me and said Garrett had an advanced stage of necrosis, and he needed to be seen as soon as possible. She set an appointment, and we cleared our calendars to make it to Dallas for a perfusion MRI and consultation with Dr. Kim.

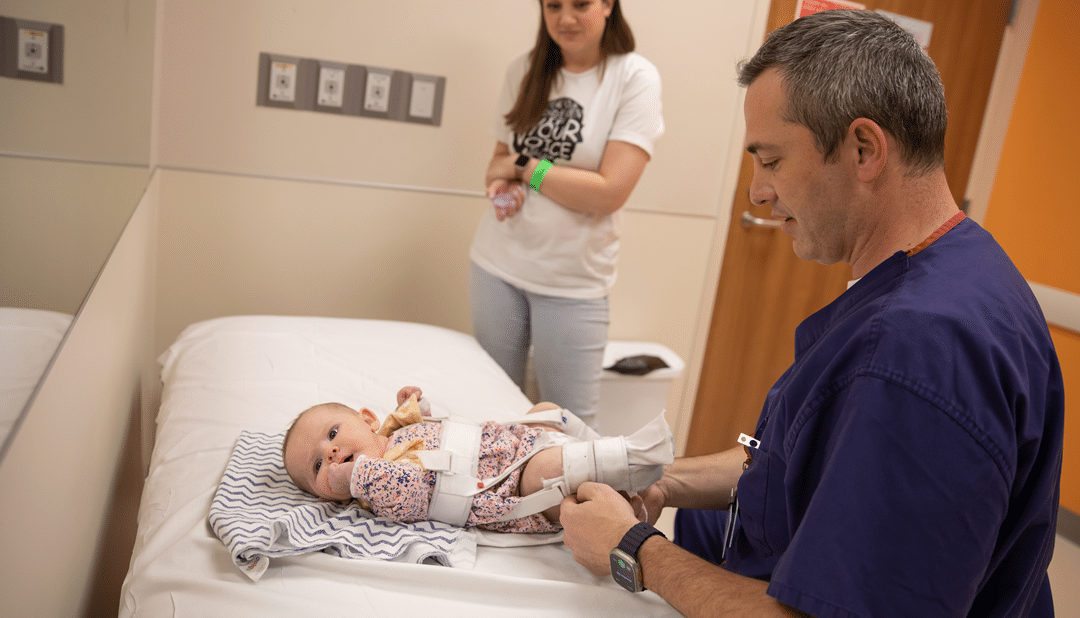

Dr. Kim reviewed his MRI. Garrett’s femoral head had completely collapsed in a period of about four months. He was a more challenging case, but Dr. Kim felt like we could, with treatment and surgery, get the best outcome if we stayed the course. On our drive home, I remember telling my husband that any guilt I had for seeking additional opinions was gone the moment Dr. Kim started explaining the treatment options. He was both conservative in his explanation but also gave me a sense of hope, too. He was clear that Garrett would end up in a wheelchair for a while, and he would need surgery. He wanted to do a tenotomy and a bone-marrow drilling to relieve some of the inflammation and tightness and then apply a Petrie cast to keep the hip in a certain placement as the first step. I clearly remember crying with Garrett at the thought of this massive contraption on my child. Dr. Kim had an opening for surgery in one week, and we jumped at the chance to get started.

The first surgery went as planned. Nothing can prepare a child for waking up and being in a double-leg cast. However, the care team at Scottish Rite was amazing from the beginning. The Child Life staff brought in a mobile game console pre-surgery, and Garrett played some video games to take his mind off of the surgery. The day after his surgery, Child Life took him to the playroom area with games, toys, art projects, etc., for a few hours, and it was a blessing for me to get some rest.

Dr. Kim checked on him, and Garrett felt like a VIP by ordering his meals via the phone. As we prepared to leave after a few days, the Occupational Therapy and Physical Therapy staff took great care to show us how to get Garrett in and out of our car and worked with us to get to the bathroom, use the new (and massive) wheelchair, and prepare ourselves to go home and manage this new lifestyle for the next six weeks.

Garrett couldn’t go to school normally during that first casting. The classroom doors were not wide enough to accommodate the platform that his legs had to rest on in the wheelchair. Every time we had to move him, we had to pick him up, take off the platform, push the wheelchair through the door, reinstall the platform, and then put him back in the wheelchair. It really is as daunting as it sounds. My husband Chad and I were very worried about the social toll this would take on Garrett. His teacher and the school administration were helpful and even had some home-tutoring set up. Garrett went to school for about four hours on a Tuesday each week to get in math and reading instruction.

The six weeks passed relatively quickly, and we didn’t stay inside and stay home. Our family is busy, and that’s an understatement. We run a small business, we work at lots of festivals and events, and we were not going to let this disease just stop us in our tracks. We were determined to make sure Garrett still interacted with people and was part of our lives as always. We took him to events, and he ran the cash register. He went fishing with his cousins. We hosted a video game birthday party with his friends where we just let them take over the living room and stay up as late as they could binging on junk food.His first cast came off in mid-November. It was joyous, and he was able to stay cast-free through the holidays.

We traveled back to Scottish Rite in early January and met with Dr. Kim. Unfortunately, Garrett had developed some stiffness and inflammation, and we couldn’t do an osteotomy as soon as we hoped. After correcting some issues with his brace, Garrett was cleared for his osteotomy soon after. He had to have a triple hip osteotomy instead of a femoral osteotomy. It’s more invasive and requires two doctors to work together to perform the surgery. Dr. Kim’s amazing staff was looking at scheduling for us in advance and noticed there was one appointment available with both doctors … the next week. So, we made another quick trip home and prepared for surgery.

Because the surgeons knew the danger of falling and damaging the work they were about to do, Garrett would have a spica cast that would encompass his right leg and entire torso. I thought Garrett was going to jump through the ceiling. I calmed him down and promised to get him to a Dallas Mavericks game eventually, if he would just understand that the doctors needed to do this casting to give his hip the best chance of recovery without damage. The surgery went well, and Garrett actually went to school five days a week for five weeks in his spica cast without issues.

Now, we are in the “waiting phase” of this dreadful disease. We hope the surgeries are done. We’re just waiting to see progress and bone growth. We hope surgery and casting is over, but we will follow Dr. Kim’s lead and trust his judgement. We pray every day for strength, patience, guidance and healing. We know this is out of our hands, and we are not in control, but we have picked the best team and talent to help us manage this difficult period. We can’t wait to return to the activities he loves. I know I will cry buckets of tears the day he steps back on the basketball court. As another Perthes mom told me, “This is a disease you never knew about and never thought you’d deal with, but here we are, and at least there are people surrounding you to help.”

This past summer, Garrett went to Camp Perthes in Minnesota! He got to meet others with Perthes and spend five days at camp doing kid things. The camp was started by Earl Cole, the winner of Survivor: Fiji. Earl Cole had Perthes as a child and used some of his winnings to start Perthes camp. He’s an example of someone who went through this disease, and he wants to help others do the same. And Earl Cole was raised in Kansas City, Kan—-small world! Garrett had a wonderful time spending time with other Perthes kids, enjoying activities like canoeing and rope courses.

Garrett started beekeeping with his dad during the pandemic. He was in first grade, and he has his own Facebook page where he captured his beekeeping adventures. We plan to get back to his Itty Bitty Beekeeper page and keep chronicling his adventures when he is released from treatment. His page is here: https://www.facebook.com/ittybittybeekeeper.

Right now, with Perthes disease, we allow him way more video game time than we want. However, it keeps him social and interacting with kids on the weekends when he would normally be at a sports practice or outing. Once we get released from treatment, we will encourage him to return to his beloved sports. He told him that his focus, when healed, is to become the best basketball player he can be.

DO YOU HAVE A STORY? WE WANT TO HEAR IT! SHARE YOUR STORY WITH US.