- A study published in 2021, “Elbow Overuse Injuries in Pediatric Female Gymnastic Athletes: Comparative Findings and Outcomes in Radial Head Stress Fractures and Capitellar Osteochondritis Dissecans,” specifically addressed findings in 58 elbows in gymnasts (average 11 years of age) treated at Scottish Rite for Children throughout a course of five years. This study was the first to describe the differences between OCD and radial head stress fractures.

Learn more about OCD of the elbow, its causes, symptoms, treatment, and prevention below.

What is osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow?

The surfaces of the bones inside joints are covered with a smooth, gliding surface called cartilage. Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a condition in which an area of cartilage and the underlying bone begin to soften, crack, or even separate. If left untreated, OCD can cause further damage to the cartilage in the joint and early arthritis.

This is a rare condition that most often affects the knee, but it can also affect the elbow, hip or ankle. In the elbow, the surface on the end of the humerus, the capitellum, is the most affected. This is typically seen in active individuals ages 8 to 19, more often boys than girls.

How does elbow OCD occur?

There are likely several factors, and the exact cause is still unclear. A common cause is a temporary loss in blood supply to an area of bone in a growing child, often combined with repetitive joint impact (overuse). There may be a genetic cause as well. Athletes at risk also often have a history of early sport specialization and year-round training. Some may report a history of a minor injury, but this is likely not the cause of the OCD lesion.

What are the signs and symptoms of OCD in the elbow?

OCD may be present even if there are not symptoms. An asymptomatic OCD lesion, one that does not cause any symptoms, may be identified when evaluating another concern. Signs and symptoms vary and may include:

- Pain that worsens with activity

- Popping or clicking

- Swelling

- Fluid inside the joint

- Catching or locking with movement

- Limited motion

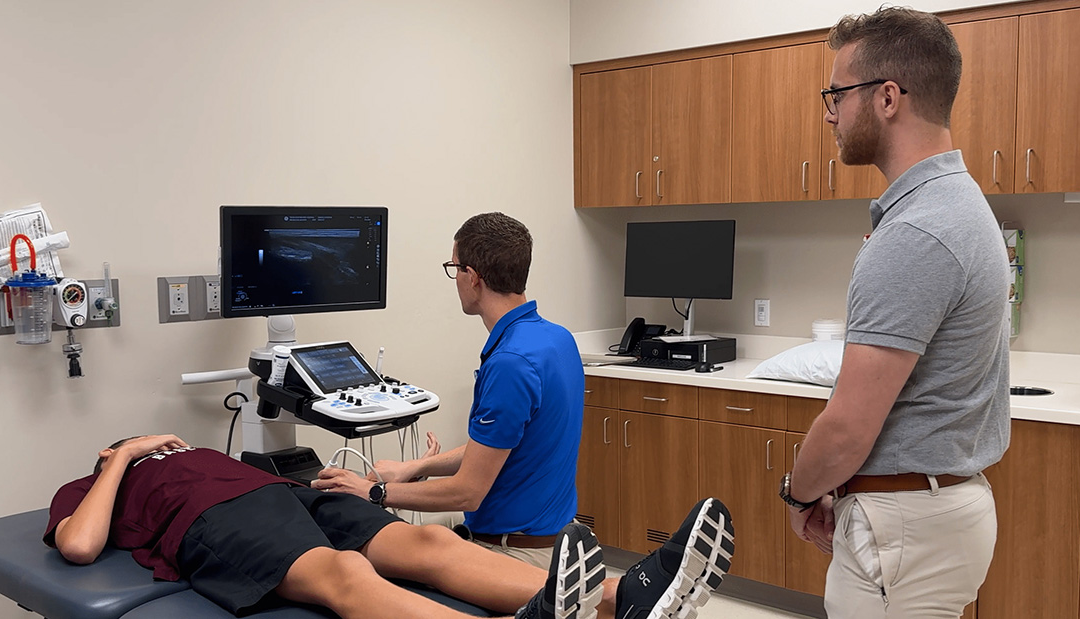

How is elbow OCD diagnosed?

Physical examination, history, and X-rays are used to diagnose OCD in the elbow. Advanced imaging, such as an MRI, is often necessary to fully assess the condition and determine treatment options.

How is elbow OCD treated?

Properly treating and managing osteochondritis dissecans in the elbow lowers the risk of long-term damage to the joint. With diagnosis and treatment in the early stages, tissues may heal with rest and limiting activities that cause pressure on the OCD lesion.

Athletes benefit from continued training while resting their elbows. It is important for our team to help them understand what activities are safe and will not cause further problems on the elbow. Examples of activities to continue while receiving treatment for elbow OCD include:

- Jogging

- Stationary bike

- Core strengthening

- Lower body weightlifting of resistance training

- Swimming

- Golf putting only

These “weightbearing” activities are not allowed because they put pressure directly on the area of the OCD lesion:

- Sports of any kind

- Handstands

- Tumbling

- Push-ups, planks

- Upper body weightlifting or resistance training

When may surgery for elbow OCD be needed?

Many elbow OCD lesions can improve with conservative, nonoperative treatment. However, surgery may be necessary if the:

- The OCD lesion appears loose, unstable, or large.

- Cartilage becomes loose in the joint.

- Imaging shows an advanced or worsening condition.

- Symptoms are worsening despite nonsurgical treatment.

What kinds of procedures are used to treat OCD in the elbow?

The choice of surgical procedure depends on the condition of the tissues at the time of surgery. Most procedures are performed using an arthroscope, a camera, and tools inserted through small incisions, but a large surgery may be needed in some cases. Our sports medicine pediatric orthopedic surgeons are experts at treating OCD and can walk you through what to expect.

Procedures that may be offered alone or in combination include:

- Drilling – drilling holes into the bone to increase blood flow and healing.

- Stabilizing – inserting a screw, suture, or other piece of hardware to keep loose tissue in place.

- Grafting – placing biological tissue in the area.

What can be expected after surgery for elbow OCD?

Our sports medicine experts work with every patient to develop an individualized postoperative treatment plan. After surgery, closely following postoperative instructions will protect the joint while the tissue is healing. Exercise and activity recommendations will be different for every patient.

How long does OCD in the elbow last?

Each case is unique, and the timing of returning to normal activity or sports will be discussed with your sports medicine physician, surgeon, or advanced practice provider. Symptoms may last months or years. It’s very important to understand that symptoms may return if the area does not fully recover before returning to repetitive or weight-bearing activities.

How can elbow OCD be prevented?

Overuse injuries like OCD occur with a high volume of training, repetition of certain movements, and early specialization in a sport.

These suggestions can help to prevent elbow OCD and other similar conditions:

- Learn how to moderate training loads and intensities.

- Make time for free play and lifetime sports like tennis, golf, cycling, and hiking.

- Take breaks weekly and between seasons.

- Learn to properly warm up and perform conditioning for your sport.

Learn more about sport specialization and preventing overuse injuries in young athletes.