Does a Discoid Meniscus Injury Need Surgery?

A discoid meniscus is an abnormally shaped piece of cartilage found in the knee joint, and due to its shape, twisting knee movements can sometimes cause it to tear. When determining whether treatment for this injury is necessary, it is important to consider why, when and how the condition was discovered.

What is a meniscus?

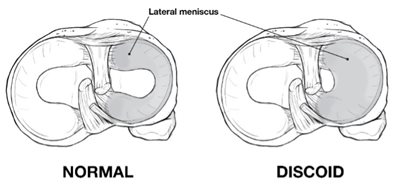

The round end of the femur (thigh bone) sits on the flat top of the tibia (shin bone) to make up the knee joint. The femur is supported by the meniscus, which is composed of two soft “c” shaped cartilage structures. They act like soft cushions that help support the knee joint. The one that sits on the inner side is called the medial meniscus, and the one on the outer side is called the lateral meniscus.

What is a discoid meniscus?

Instead of having the typical “c” shape, a discoid meniscus forms as a solid piece, like a disc or a Frisbee®. The tissue grows thicker and larger than a normal meniscus and also has an abnormal texture, which makes it more likely to cause problems.

What causes a discoid meniscus?

A discoid meniscus is a congenital (at birth) defect and does not grow into the normal shape. This defect is not caused by trauma (i.e., an accident) or an injury. One to two out of every 100 children have a discoid meniscus. The condition is found more often in boys.

A discoid meniscus cannot be prevented. As the child grows, injuries and/or changes in the alignment of the hip, knee and ankle may cause symptoms.

What are the symptoms?

A discoid meniscus does not always cause symptoms. It may go unnoticed until symptoms begin. Symptoms can include pain, popping or snapping, limping, inability to bear weight (stand or walk) and inability to straighten the knee.

How is a discoid meniscus diagnosed?

A thorough history and physical examination are used to diagnose a discoid meniscus. Common findings on the outside of the knee (lateral joint line) include a bulge that can be seen or a “snap” that can be felt and heard.

X-rays are used to look at the alignment of the bones in the knee and leg. Other imaging, such as an MRI, may be used to look at the condition of the meniscus and other tissues in the knee.

What is the treatment?

For children who do not have symptoms or if they have a “clunk” when they move their knee, yet do not experience pain or difficulty conducting daily activities, no treatment is needed.

Early symptoms, such as swelling and pain, can be managed by resting, elevating the leg and other common strategies for knee injuries, such as ice and anti-inflammatory medications.

Surgical treatment is needed if there is a concern regarding the development of the knee with a large discoid or when symptoms begin to interrupt daily activities.

A knee arthroscopy, a type of minimally invasive surgery, may be recommended. The goal of surgery is to improve the shape of the meniscus and remove any loose or extra tissue that may cause the joint to become stuck. Rehabilitation and a slow return to sports may be necessary after surgery to change the shape of the meniscus.

A discoid meniscus increases the risk of a meniscal tear, and therefore, the condition is often found when evaluating an MRI of the knee after an injury. In these cases, treatment may be recommended to improve the shape of the meniscus. This can be done at the same time as surgery for other problems diagnosed in the knee.

What is the long-term outlook?

A discoid meniscus should not prevent normal daily activities or participation in sports. Diagnosis and management of symptoms can reduce the risk of further damage in the knee joint and prevent long-term problems. Regular follow-up to monitor the growth and health of the developing joint is very important after diagnosis, even if treatment is not needed in the early stages.

An important initiative of the Center for Excellence in Sports Medicine team at Scottish Rite for Children is a quality improvement registry designed to learn about the care and outcomes of treatment for discoid meniscus, among other conditions. This multi-center collection of data is led by pediatric orthopedic surgeon and director of clinical research Henry B. Ellis, M.D., is called the Sports Cohort Outcomes Registry (SCORE).

“This large collection of data allows us to compare surgery findings and outcomes across different age groups. The data set is unlike any other and will help to define care for this condition and many others. Early results were shared at the Pediatric Research in Sports Medicine annual meeting in 2022 and have already shaped more studies and better patient care.”

– Henry B. Ellis, M.D.

Each institution in the SCORE group may take care of a handful of patients with this condition each year. The compiled data, reviewing nearly 300 patients and their outcomes helps to provide better education to patient-families, improve surgical decision-making and setting better expectations for outcomes.

Differences in the appearance of the meniscus as well as the ability for the meniscus to be repaired were apparent. In younger patients, the meniscus:

- Is larger and covers more of the bone.

- May have loose, unstable edges.

- Is more likely able to be repaired.

These early findings help pediatric orthopedic surgeons know what to expect and how to counsel parents about who may or may not need surgery. Ultimately, the registry will be able to provide standard outcome expectations which will further improve the patient experience and outcomes.