Aug 04, 2021 / Hip Disorders

A Shared Bond: Expert Hip Care Across Generations

Cover story previously published in Rite Up, 2021 – Issue 2.

by Hayley Hair

After a decade has passed, former patient Cristal says she felt the familiarity walking the halls of Scottish Rite for Children again. Navigating to the colorful registration desk as she had many times before, she would not be giving her name to check in this time but that of her newborn son, Alonso. “When I first came with him, it brought back memories of when I was little,” Cristal says.

At Alonso’s two-week checkup, his pediatrician found a problem with his hips. “He would open his hips a little bit on his own, but when the doctor would try to check his joints properly, he would really cry,” Alonso’s dad, Oscar, says. The pediatrician referred the family to Scottish Rite, and as suspected, the diagnosis was developmental dysplasia of the hip or DDH. This hip condition occurs in one to two percent of births and is the result of the femoral head and acetabulum, or the ball and socket, of the hip joint not developing normally.

Cristal was treated at Scottish Rite for DDH and a condition affecting her feet after she was born, requiring a few surgeries. She was a patient of former assistant chief of staff and consulting physician John G. Birch, M.D., FRCSC, until she graduated high school. “One of the special things about being a pediatric orthopedic surgeon is you establish a relationship with the family, and you watch that child grow up,” Birch says.

Alonso’s pediatric orthopedic surgeon, William Z. Morris, M.D., focuses on hips, lower extremity and general orthopedics at Scottish Rite and has worked with the family to reorient and repair his hips. “With DDH, the socket ends up being a little bit shallow, causing it to not cover the ball as well or as deeply as it should,” Morris says. “This condition can present in babies, or in adolescents, as a slightly shallow socket all the way up to a hip that is fully dislocated.”

Confirming DDH in infants takes into account many considerations, but there are risk factors parents should be aware of that increase the likelihood of DDH. Morris says what doctors look for are the four F’s — female, first-born, family history and feet first or breech presentation — and extra care should be taken regarding hip development with these factors.

Environmental causes play a role in how the hips develop as well. “There’s a lot of importance in how we take care of our babies’ hips after they’re born,” Morris says. “Swaddling the legs in a forced extension can cause the hips to develop incorrectly. The ball and the socket are almost like moldable pieces of clay when you are young, so letting the hips and legs move into a flexed and separated position helps keep the ball tucked up in the socket and makes the socket deeper and the ball more round.” When swaddling your baby, focus on wrapping the arms and upper torso only, allowing the hips and legs to move without constriction.

Early intervention with DDH is important. “Parents should know that DDH caught early is treated very successfully,” Morris says. “And the vast majority of the time we can do so without surgery.” Even severe cases, where the hip is fully dislocated, are treatable with a harness or brace more than 80% of the time.

The goal for any DDH treatment is to put the ball back into the socket deeply so the hip can develop. The most common nonsurgical treatment option for babies with DDH is the Pavlik harness – a soft, fabric brace that keeps the hips in a “frog-like” position that holds the ball in the hip socket. For patients who require surgical intervention, the child is put under anesthesia while the pediatric orthopedic surgeon manipulates the ball into the socket and then applies a cast, which acts like a permanent brace. This helps the hip joint stay in place while the surrounding tissues and ball and socket remodel. That is known as a closed reduction. If the closed procedure does not successfully put the ball into the socket, the surgeon might need to make an incision to address the obstacles preventing the ball from seating deeply in the socket. This is known as an open reduction.

Following weeks of wearing a Pavlik harness without improvement in Alonso’s hips, Alonso and his family were offered surgery. In February, Alonso had a bilateral closed reduction procedure, and he was in a spica cast that holds both legs open in a butterfly position to keep the hips stable in their reduced position. Spica casts require special car seats and strollers, but Cristal says they found ways to stay mobile. “He managed to move around in the cast,” she says. “He found his little ways to get to things.”

Alonso stayed in the cast for 14 weeks. “We were really counting down to getting his cast off,” Cristal says. “It was getting closer, and we were saying only one more week, only one more day.”

In May, his cast removal appointment was exciting for several reasons. Morris invited a special guest, and it was a happy reunion when Birch, Cristal’s doctor, popped in to say hello to his longtime patient and to meet her baby. When the door opened and Cristal saw a familiar face from a decade earlier, she excitedly said, “Dr. Birch!”

“It’s very cool that two generations are getting cared for at Scottish Rite,” Morris says. While talking together, Birch adds, “Two generations of patients and two generations of surgeons together.”

Morris will continue to follow Alonso’s progress throughout his growing years. His parents have a RhinoTM brace for Alonso to wear when he’s sleeping and napping.

Next steps for Alonso — getting back to doing what he loves, and his parents know one activity they are sure to see. “He loves to dance,” Cristal says. “He’ll dance to any type of music, and even with the cast on, it didn’t stop him at all.”

For advice to parents just starting their journey with DDH, Cristal and Oscar have some reassurance. “Trust the doctors. They know what they are doing,” Oscar says. “At the end of the day, everyone wants what is best for the child.”

Read the full issue.

by Hayley Hair

After a decade has passed, former patient Cristal says she felt the familiarity walking the halls of Scottish Rite for Children again. Navigating to the colorful registration desk as she had many times before, she would not be giving her name to check in this time but that of her newborn son, Alonso. “When I first came with him, it brought back memories of when I was little,” Cristal says.

At Alonso’s two-week checkup, his pediatrician found a problem with his hips. “He would open his hips a little bit on his own, but when the doctor would try to check his joints properly, he would really cry,” Alonso’s dad, Oscar, says. The pediatrician referred the family to Scottish Rite, and as suspected, the diagnosis was developmental dysplasia of the hip or DDH. This hip condition occurs in one to two percent of births and is the result of the femoral head and acetabulum, or the ball and socket, of the hip joint not developing normally.

Cristal was treated at Scottish Rite for DDH and a condition affecting her feet after she was born, requiring a few surgeries. She was a patient of former assistant chief of staff and consulting physician John G. Birch, M.D., FRCSC, until she graduated high school. “One of the special things about being a pediatric orthopedic surgeon is you establish a relationship with the family, and you watch that child grow up,” Birch says.

Alonso’s pediatric orthopedic surgeon, William Z. Morris, M.D., focuses on hips, lower extremity and general orthopedics at Scottish Rite and has worked with the family to reorient and repair his hips. “With DDH, the socket ends up being a little bit shallow, causing it to not cover the ball as well or as deeply as it should,” Morris says. “This condition can present in babies, or in adolescents, as a slightly shallow socket all the way up to a hip that is fully dislocated.”

Confirming DDH in infants takes into account many considerations, but there are risk factors parents should be aware of that increase the likelihood of DDH. Morris says what doctors look for are the four F’s — female, first-born, family history and feet first or breech presentation — and extra care should be taken regarding hip development with these factors.

Environmental causes play a role in how the hips develop as well. “There’s a lot of importance in how we take care of our babies’ hips after they’re born,” Morris says. “Swaddling the legs in a forced extension can cause the hips to develop incorrectly. The ball and the socket are almost like moldable pieces of clay when you are young, so letting the hips and legs move into a flexed and separated position helps keep the ball tucked up in the socket and makes the socket deeper and the ball more round.” When swaddling your baby, focus on wrapping the arms and upper torso only, allowing the hips and legs to move without constriction.

Early intervention with DDH is important. “Parents should know that DDH caught early is treated very successfully,” Morris says. “And the vast majority of the time we can do so without surgery.” Even severe cases, where the hip is fully dislocated, are treatable with a harness or brace more than 80% of the time.

The goal for any DDH treatment is to put the ball back into the socket deeply so the hip can develop. The most common nonsurgical treatment option for babies with DDH is the Pavlik harness – a soft, fabric brace that keeps the hips in a “frog-like” position that holds the ball in the hip socket. For patients who require surgical intervention, the child is put under anesthesia while the pediatric orthopedic surgeon manipulates the ball into the socket and then applies a cast, which acts like a permanent brace. This helps the hip joint stay in place while the surrounding tissues and ball and socket remodel. That is known as a closed reduction. If the closed procedure does not successfully put the ball into the socket, the surgeon might need to make an incision to address the obstacles preventing the ball from seating deeply in the socket. This is known as an open reduction.

Following weeks of wearing a Pavlik harness without improvement in Alonso’s hips, Alonso and his family were offered surgery. In February, Alonso had a bilateral closed reduction procedure, and he was in a spica cast that holds both legs open in a butterfly position to keep the hips stable in their reduced position. Spica casts require special car seats and strollers, but Cristal says they found ways to stay mobile. “He managed to move around in the cast,” she says. “He found his little ways to get to things.”

Alonso stayed in the cast for 14 weeks. “We were really counting down to getting his cast off,” Cristal says. “It was getting closer, and we were saying only one more week, only one more day.”

In May, his cast removal appointment was exciting for several reasons. Morris invited a special guest, and it was a happy reunion when Birch, Cristal’s doctor, popped in to say hello to his longtime patient and to meet her baby. When the door opened and Cristal saw a familiar face from a decade earlier, she excitedly said, “Dr. Birch!”

“It’s very cool that two generations are getting cared for at Scottish Rite,” Morris says. While talking together, Birch adds, “Two generations of patients and two generations of surgeons together.”

Morris will continue to follow Alonso’s progress throughout his growing years. His parents have a RhinoTM brace for Alonso to wear when he’s sleeping and napping.

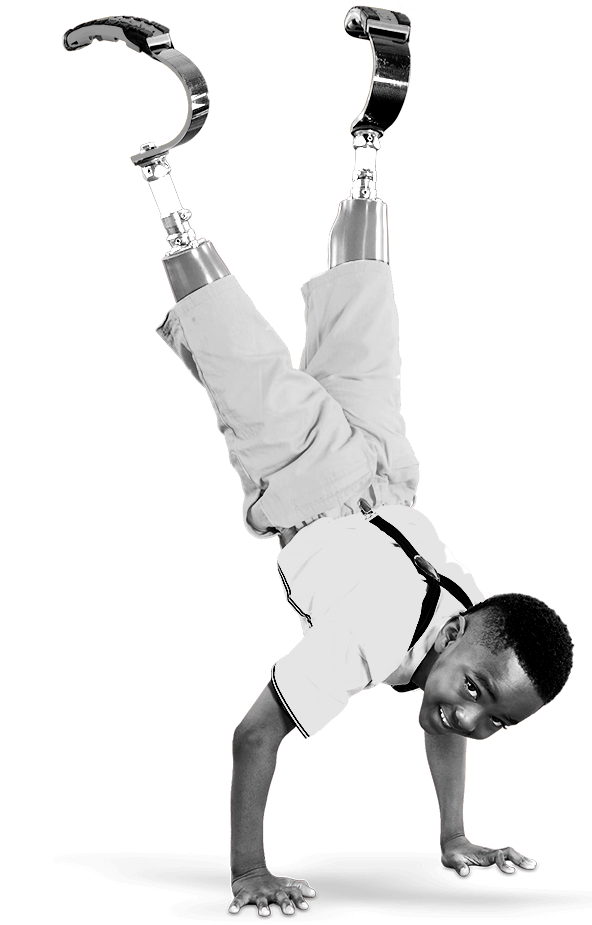

Next steps for Alonso — getting back to doing what he loves, and his parents know one activity they are sure to see. “He loves to dance,” Cristal says. “He’ll dance to any type of music, and even with the cast on, it didn’t stop him at all.”

For advice to parents just starting their journey with DDH, Cristal and Oscar have some reassurance. “Trust the doctors. They know what they are doing,” Oscar says. “At the end of the day, everyone wants what is best for the child.”

Read the full issue.